Photo by Christian Weiss

Every AI agent eventually asks for the same thing:

Let me run a program.

Sometimes it’s a harmless pytest. Sometimes it’s pip install sketchy-package && python run.py. Either way, the moment you let an agent execute code, you’re running untrusted bytes on a machine you care about.

Years ago I first learned this lesson doing basic malware analysis. The mental model was blunt but effective: run hostile code in something you can delete. If it breaks out, you nuke it.

AI agents recreate the same problem, except now the “malware sample” is often:

- code generated by a model,

- code pasted in by a user,

- or a dependency chain your agent pulled in because it “looked right.”

In all cases, the code becomes a kernel client. It gets whatever the kernel and policy allow: filesystem reads, network access, CPU time, memory, process creation, and sometimes GPUs.

And “escape” isn’t the only failure mode. Even without a kernel exploit, untrusted code can:

- exfiltrate secrets (SSH keys, cloud creds, API tokens),

- phone home with private repo code,

- pivot into internal networks,

- or just burn your money (crypto mining, fork bombs, runaway builds).

The request is simple: run this program, don’t let it become a machine-ownership problem.

This isn’t niche anymore. Vercel, Cloudflare, and Google have all shipped sandboxed execution products in the last year. But the underlying technology choices are still misunderstood, which leads to “sandboxes” that are either weaker than expected or more expensive than necessary.

Part of the confusion is that AI execution comes in multiple shapes:

- Remote devbox / coding agent: long-lived workspace, shell access, package managers, sometimes GPU.

- Stateless code interpreter: run a snippet, return output, discard state.

- Tool calling: run small components (e.g., “read this file”, “call this API”) with explicit capabilities.

- RL environments: lots of parallel runs, fast reset, sometimes snapshot/restore.

Different shapes want different lifecycle and different boundaries.

There’s also a hardware story hiding here. In 2010, “just use a VM” usually meant seconds of boot time and enough overhead to kill density. Containers won because they were cheap.

In 2026, you can boot a microVM fast enough to feel container-like, and you can snapshot/restore them to make “reset” almost free. The trade space changed, but our vocabulary didn’t.

The other part of the confusion is the word sandbox itself. In practice, people use it to mean at least four different boundaries:

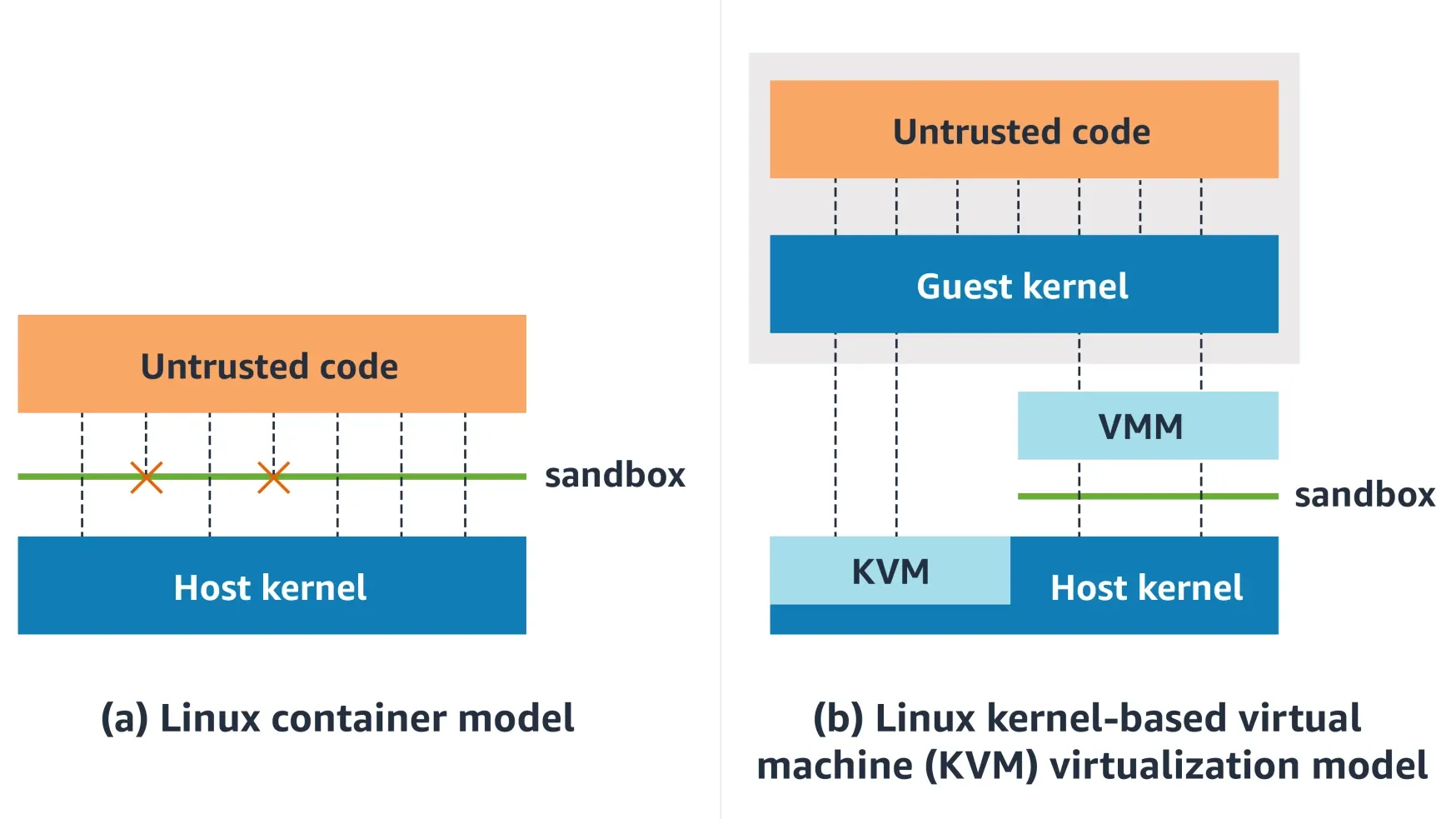

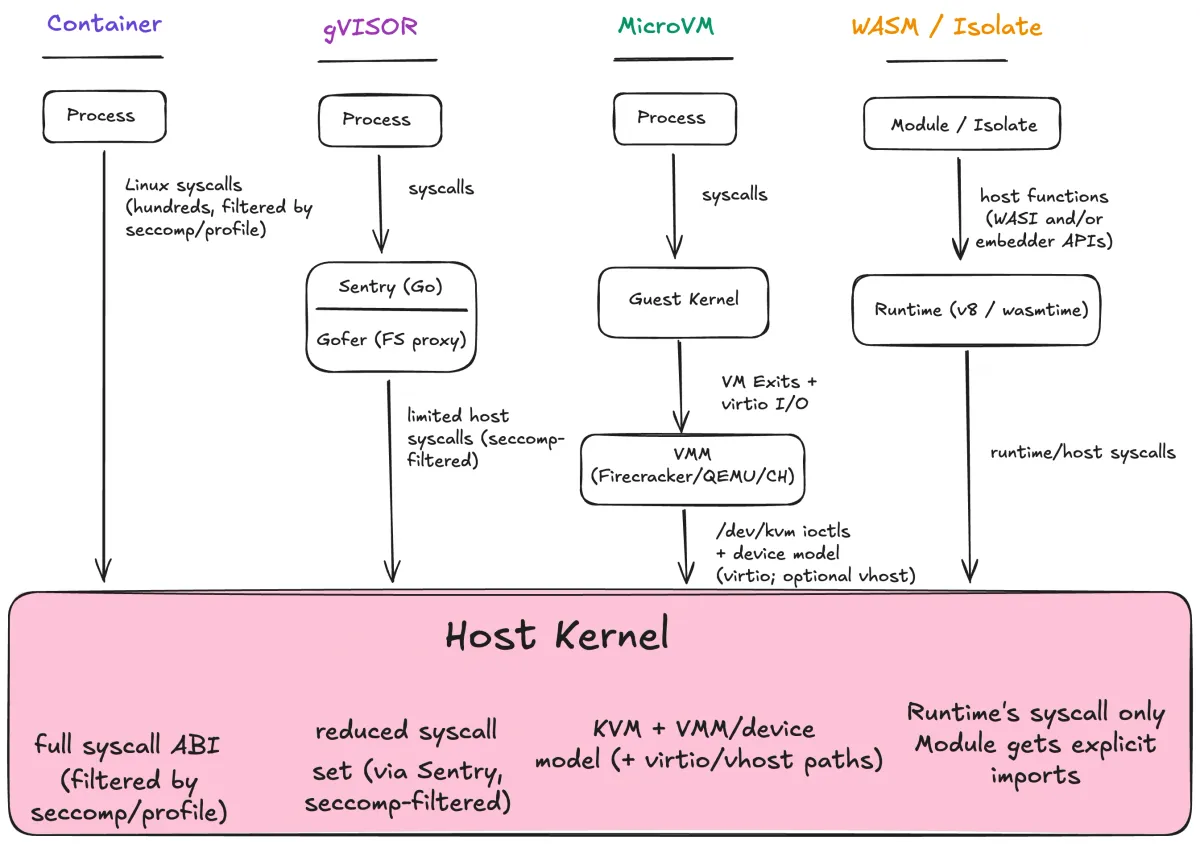

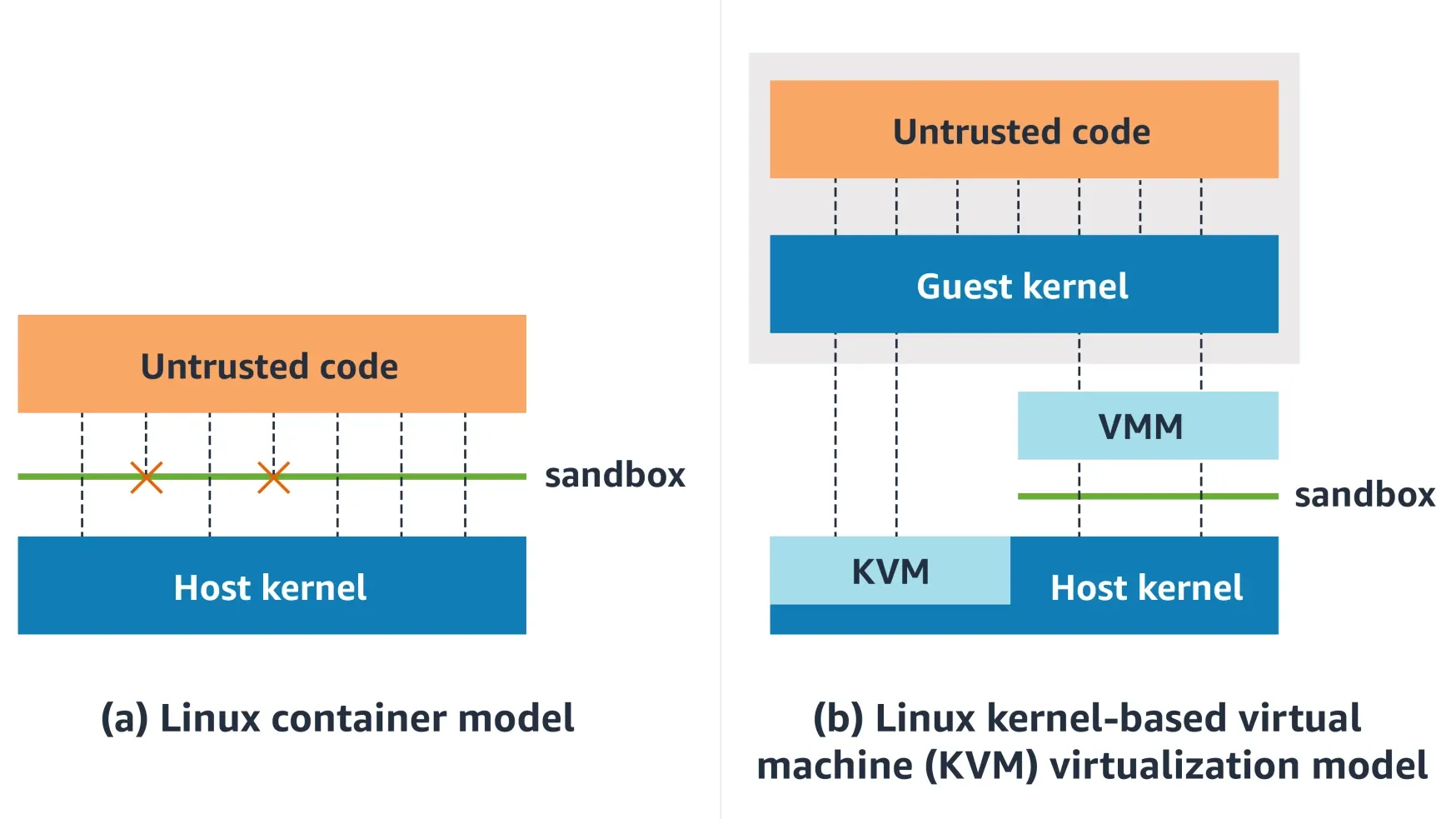

A container shares the host kernel. Every syscall still lands in the same kernel that runs everything else. A kernel bug in any allowed syscall path is a host bug.

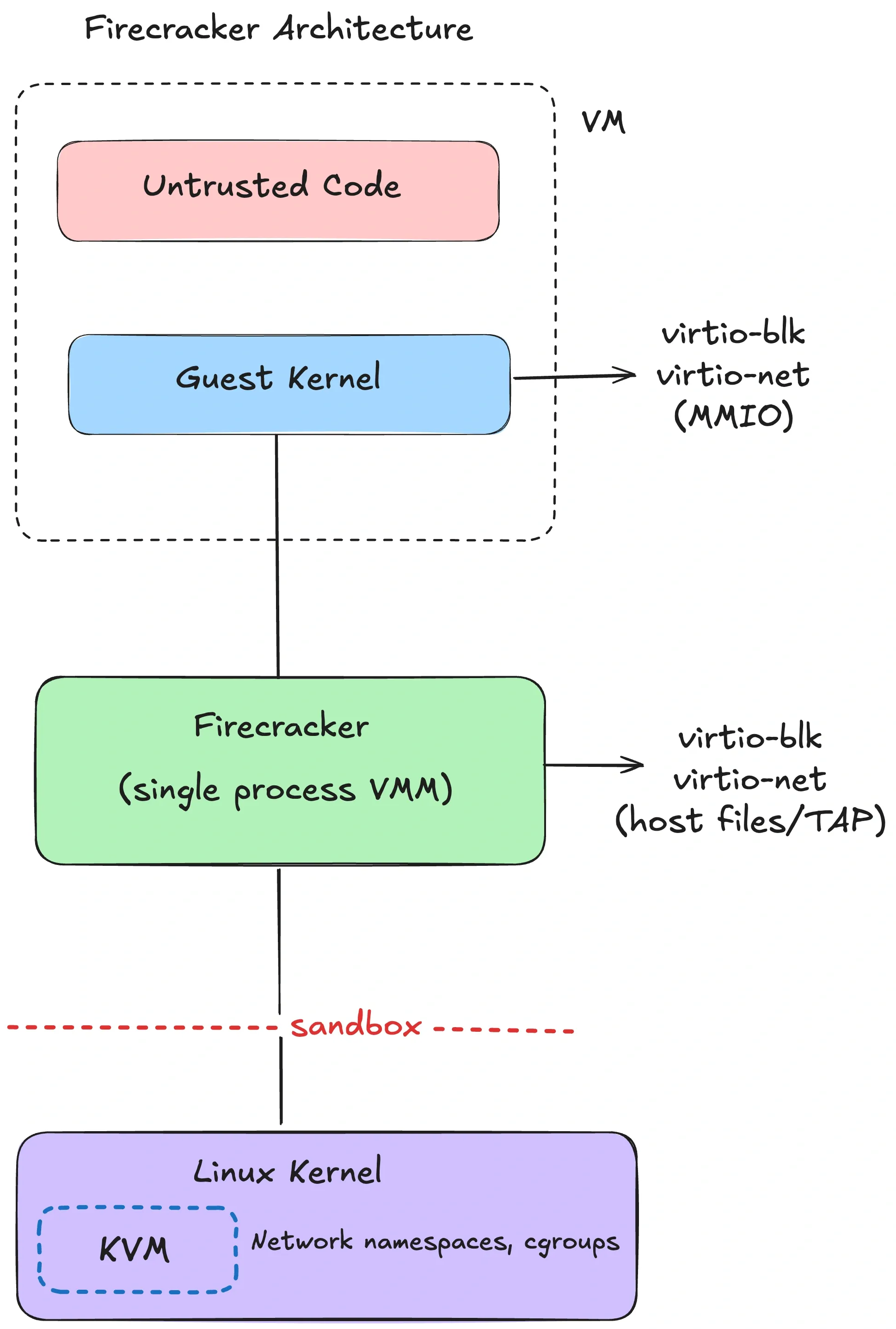

A microVM runs a guest kernel behind hardware virtualization. The workload talks to its kernel. The host kernel mostly sees KVM ioctls and virtio device I/O, not the full Linux syscall ABI.

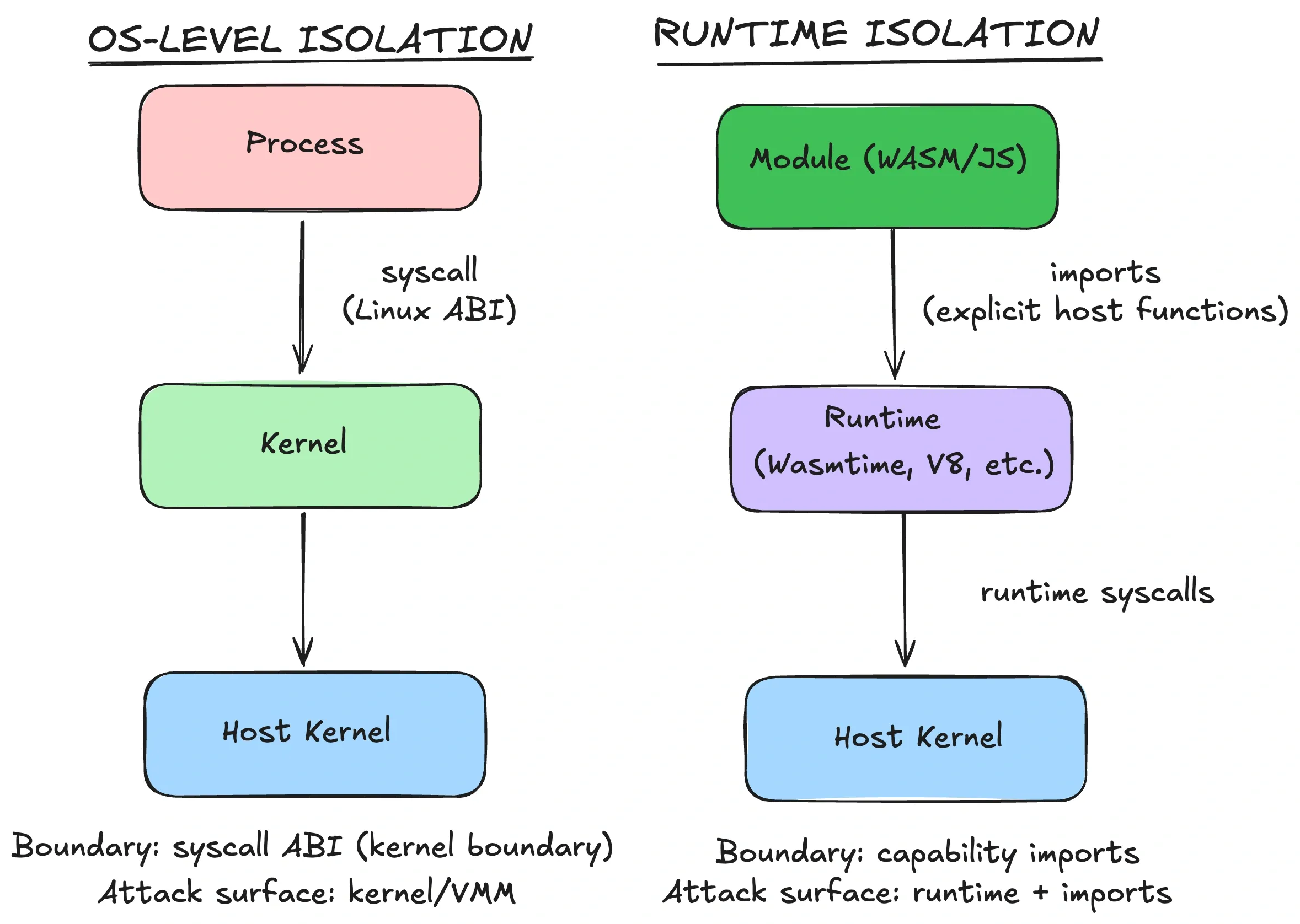

gVisor interposes a userspace kernel. Application syscalls are handled by the Sentry rather than going straight to the host kernel; the Sentry itself uses a small allowlist of host syscalls.

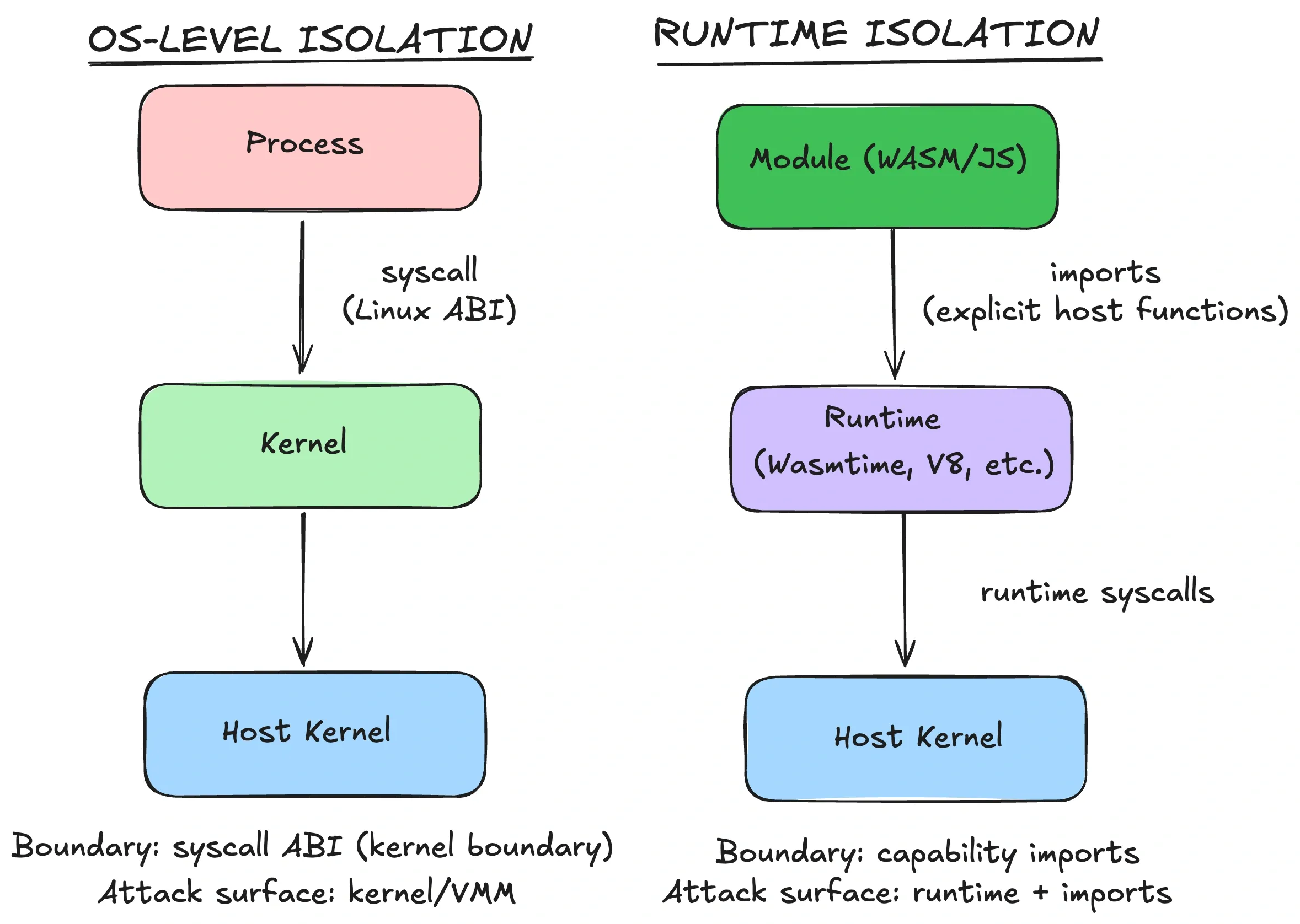

WebAssembly / isolates constrain code inside a runtime. There is no ambient filesystem or network access; the guest only gets host capabilities you explicitly provide.

These aren’t interchangeable. They have different startup costs, compatibility stories, and failure modes. Pick the wrong one and you’ll either ship a “sandbox” that leaks, or a sandbox that can’t run the software you need.

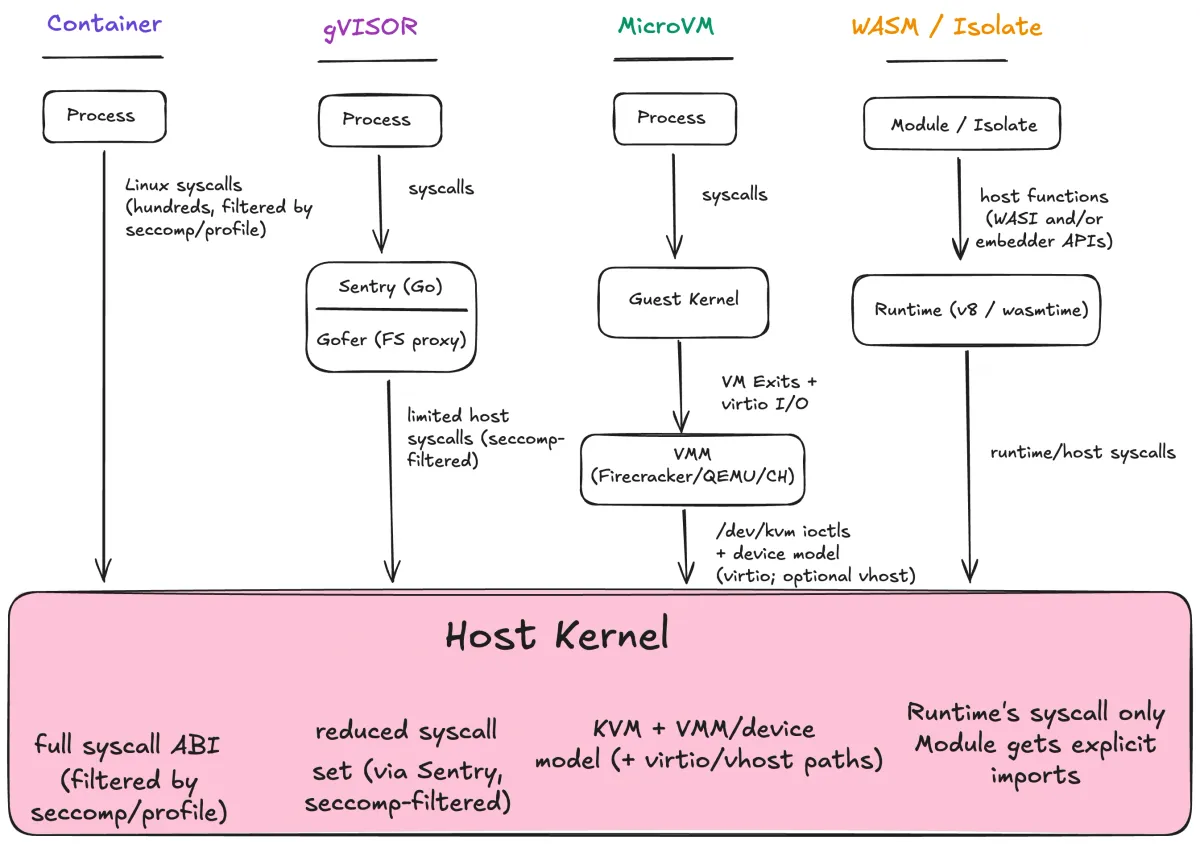

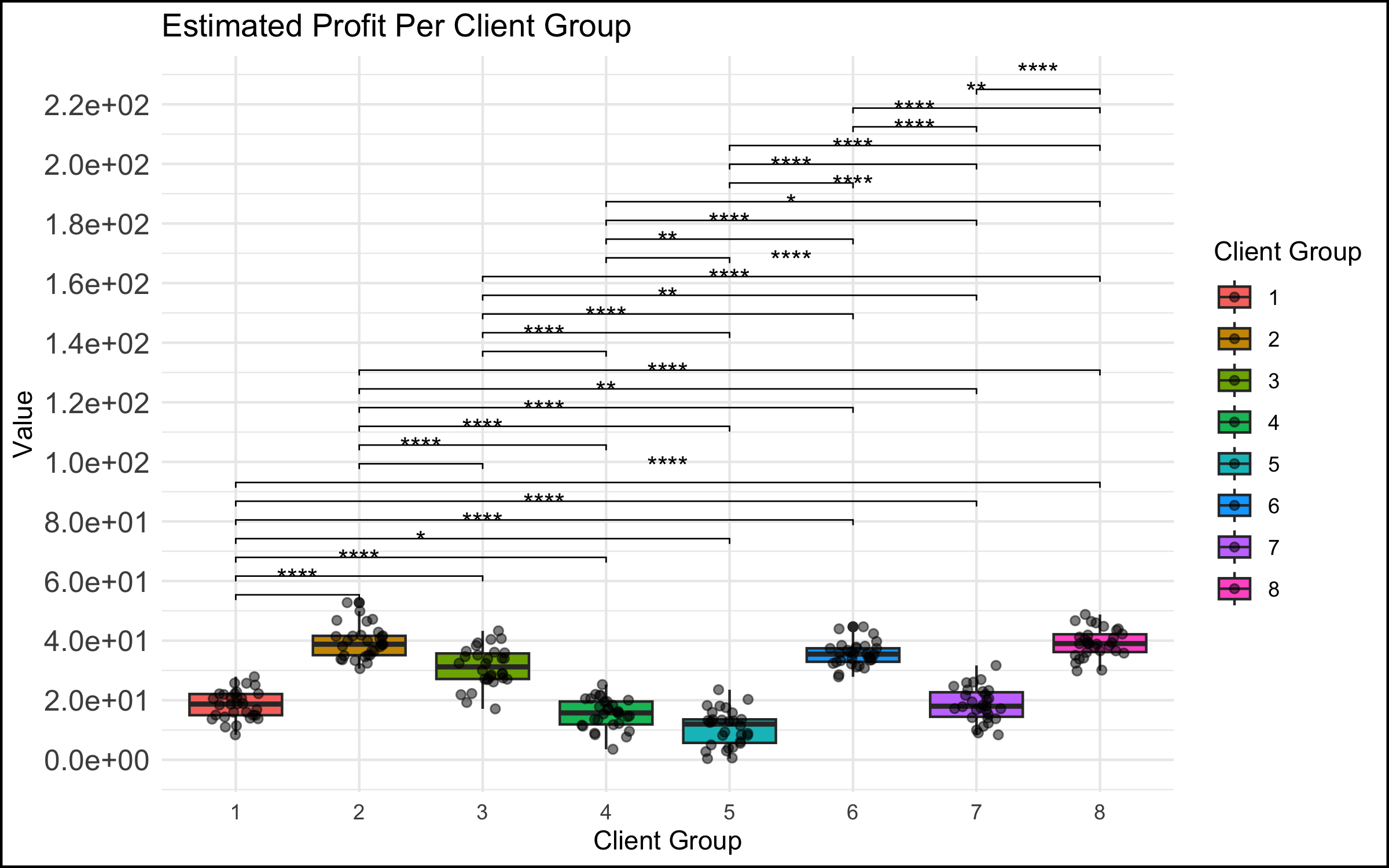

How each boundary mediates access to the host kernel. Moving left → right, direct syscall ABI exposure shrinks.

The diagram is the whole game. Containers expose the host kernel’s syscall ABI (filtered by policy, but still the same kernel). gVisor interposes a userspace kernel. MicroVMs insert a guest kernel behind hardware virtualization. Wasm modules don’t get a syscall ABI at all — they get explicit host functions.

Moving left → right, direct syscall ABI exposure shrinks.

But you don’t get something for nothing. Every “stronger” boundary adds a different trusted component: a userspace kernel (gVisor), a guest kernel + VMM (microVMs), or a runtime + embedder (Wasm). Stronger doesn’t mean simpler. It means you’re betting on different code.

If this still feels weird, it’s because the industry trained us to treat containers as the default answer.

It’s the mid-2010s. Docker is exploding. Kubernetes makes containers the unit of scheduling. VMs are heavier, slower to boot, and harder to operate. Containers solve a real problem: start fast, pack densely, ship the same artifact everywhere.

For trusted workloads, that bet is often fine: you’re already trusting the host kernel.

AI agents change the threat model as now you are executing arbitrary code paths, often generated by a model, sometimes supplied by a user, inside your infrastructure.

That doesn’t mean “never use containers.” It means you need a clearer decision procedure than “whatever we already use.”

In the rest of this post, I’ll give you a simple mental model for evaluating sandboxes, then walk through the boundaries that show up in real AI execution systems: containers, gVisor, microVMs, and runtime sandboxes.

The three-question model

Here’s the mental model I use. Sandboxing is three separate decisions that people blur together, and keeping them distinct prevents a lot of bad calls.

Boundary is where isolation is enforced. It defines what sits on each side of the line.

- Container boundary: processes in separate namespaces, still one host kernel.

- gVisor boundary: workload syscalls are serviced by a userspace kernel (Sentry) first.

- MicroVM boundary: syscalls go to a guest kernel; the host kernel sees hypervisor/VMM activity, not the guest syscall ABI.

- Runtime boundary: guest code has no syscall ABI; it can only call explicit host APIs.

The boundary is the line you bet the attacker cannot cross.

Policy is what the code can touch inside the boundary:

- filesystem paths (read/write/exec),

- network destinations and protocols,

- process creation/signals,

- device access (including GPUs),

- time/memory/CPU/disk quotas,

- and the interface surface itself (syscalls, ioctls, imports).

A tight policy in a weak boundary is still a weak sandbox. A strong boundary with a permissive policy is a missed opportunity.

Lifecycle is what persists between runs. This matters a lot for agents and RL:

- Fresh run: nothing persists. Great for hostile code. Bad for “agent workspace” UX.

- Workspace: long-lived filesystem/session. Great for agents; dangerous if secrets leak or persistence is abused.

- Snapshot/restore: fast reset by checkpointing VM or runtime state. Great for RL rollouts and “pre-warmed” agents.

Lifecycle also changes your operational choices. If you snapshot, you need a snapshotable boundary (microVMs, some runtimes). If you need a workspace, you need durable storage and a policy story for secrets.

The three questions

When evaluating any sandbox, ask:

- What is shared between this code and the host?

- What can the code touch (files, network, devices, syscalls)?

- What survives between runs?

If you can answer those, you understand your sandbox. If you can’t, you’re guessing.

A quick example makes the separation clearer:

- Multi-tenant coding agent

- Boundary: microVM (guest kernel)

- Policy: allow workspace FS, deny host mounts, outbound allowlist, no raw devices

- Lifecycle: snapshot base image, clone per session, destroy on close

Same product idea, different constraints:

- Tool calling (e.g., “format this code”)

- Boundary: Wasm component

- Policy: preopen one directory, no network by default

- Lifecycle: fresh per call

Vocabulary

Sandbox: boundary + policy + lifecycle.

Container: a packaging format plus process isolation built on kernel features. One kernel, many isolated views.

Virtual machine: a guest OS kernel running on virtual hardware.

MicroVM: a minimal VM optimized for fast boot and small footprint.

Runtime sandbox: isolation enforced by a runtime (Wasm, V8 isolates) rather than the OS.

Linux building blocks

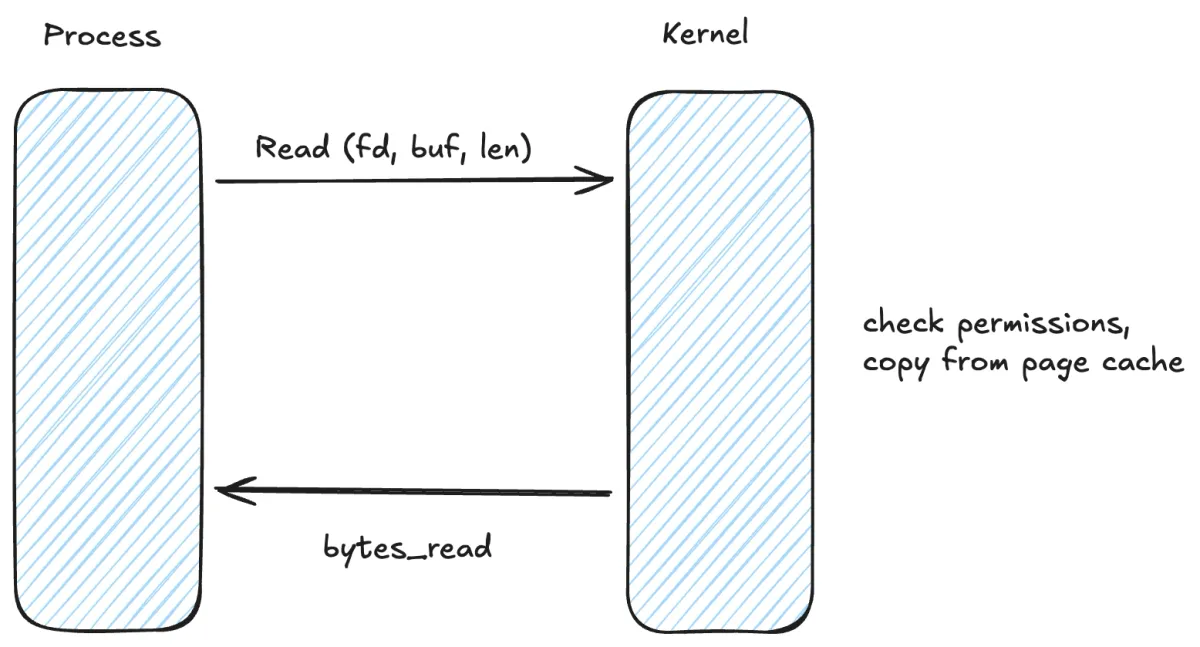

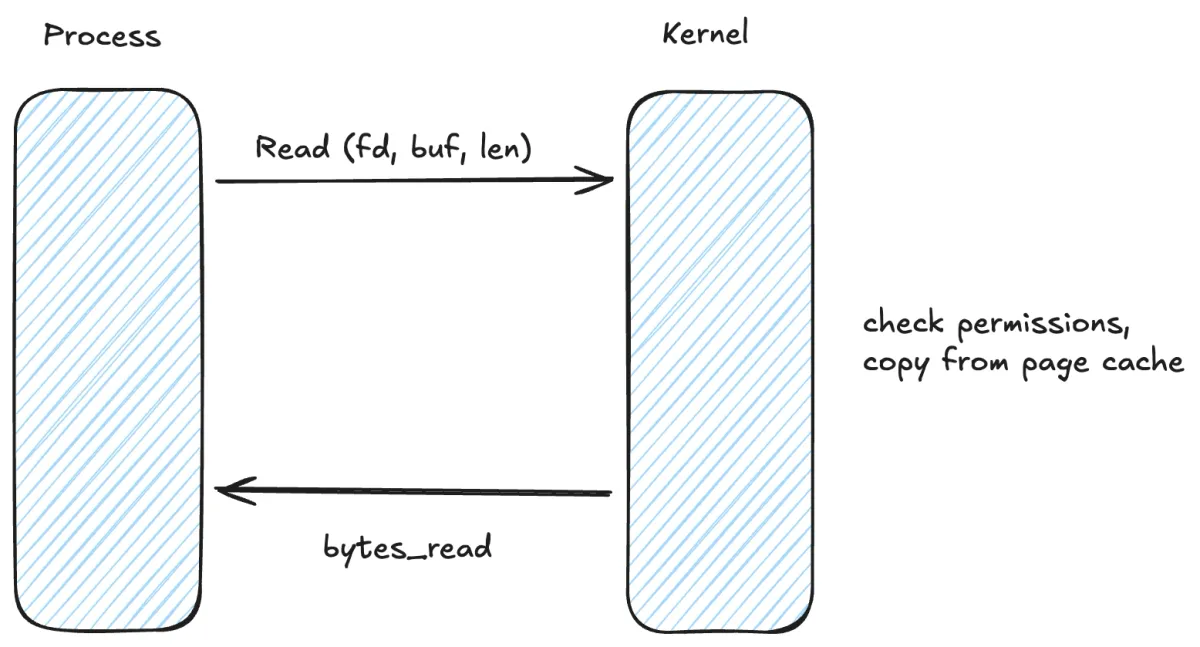

Before comparing sandbox types, it helps to be explicit about what we’re sandboxing against. A process is a kernel client.

It runs in userspace. When it needs something real — read a file, create a socket, allocate memory, spawn a process — it makes a syscall. That syscall enters the kernel. Kernel code runs with full privileges.

If there is a bug in any reachable syscall path, filesystem code, networking code, or ioctl handler, you can get local privilege escalation. That’s the root of the “container escape” story.

If you want a mental picture: the process is unprivileged code repeatedly asking the kernel to do work on its behalf. You can restrict which questions it’s allowed to ask. You cannot make the kernel stop being privileged.

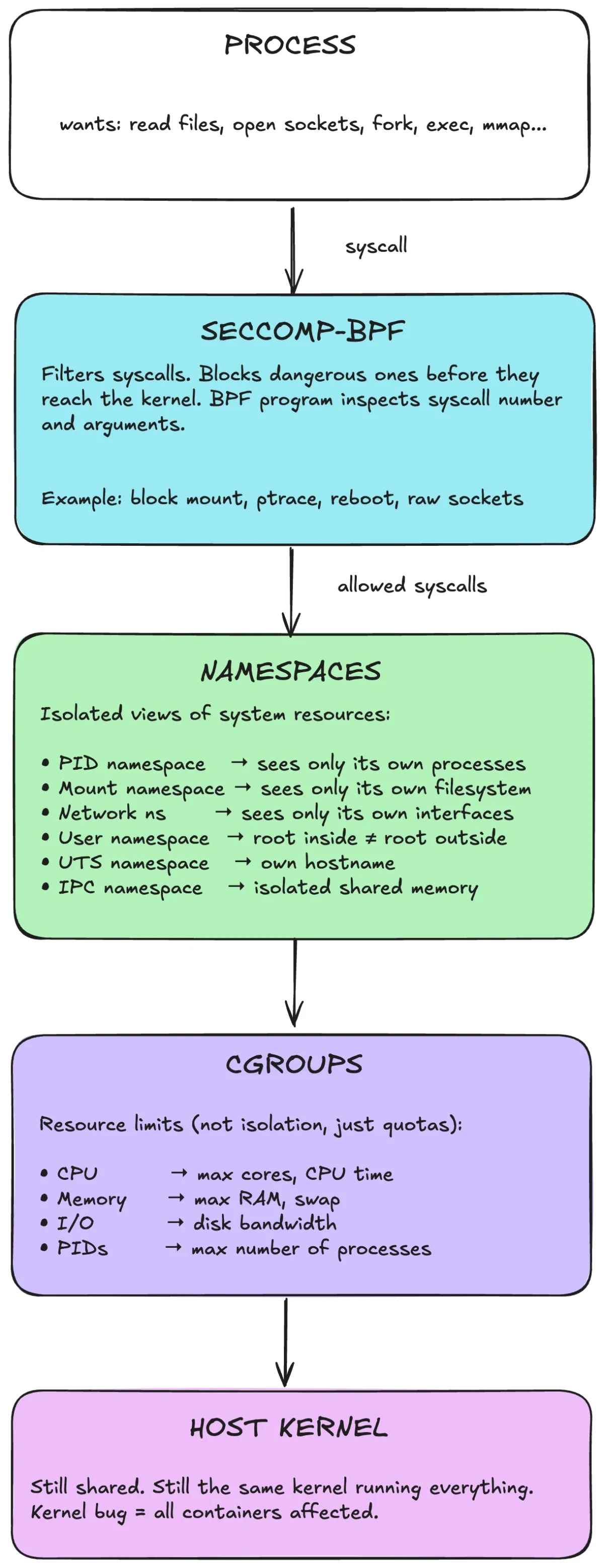

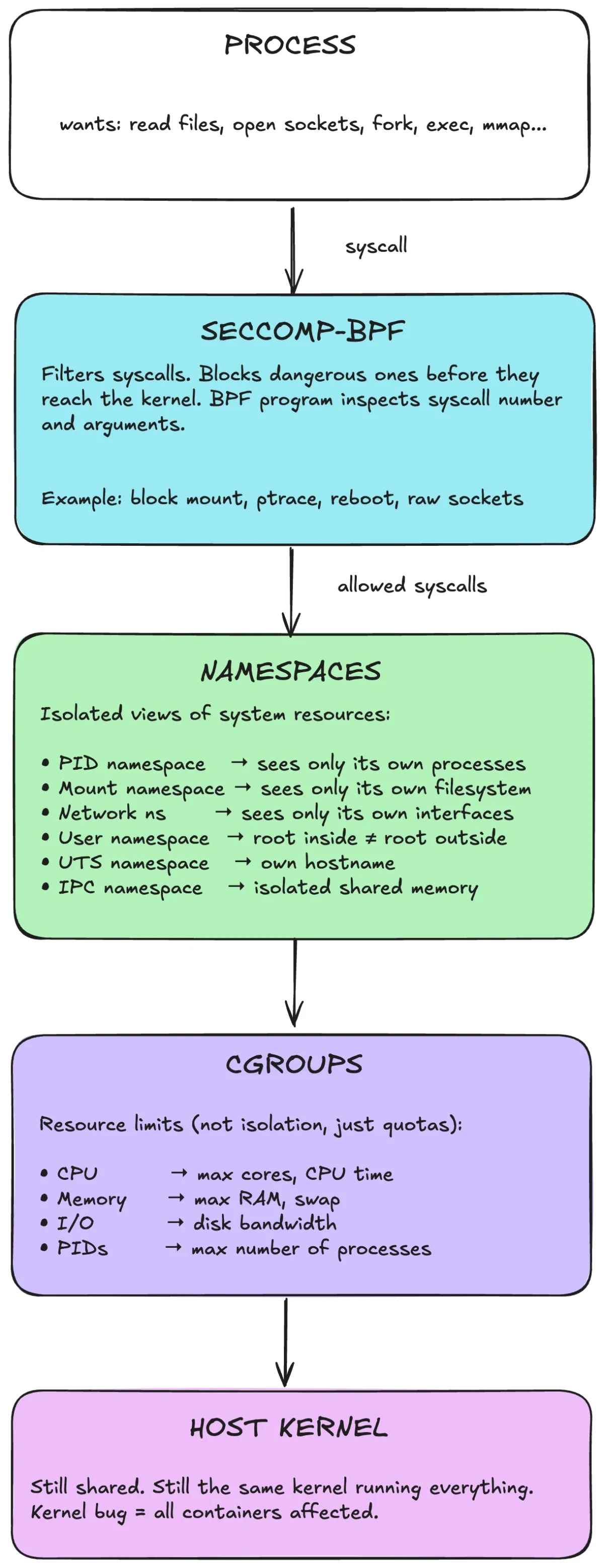

Linux containers are a policy sandwich built from four primitives:

Namespaces

Namespaces give a process an isolated view of certain resources by providing separate instances of kernel subsystems:

- PID namespace: isolated process tree / PID numbering

- Mount namespace: isolated mount table / filesystem view

- Network namespace: isolated network stack (interfaces, routes, netfilter state)

- IPC/UTS namespaces: System V IPC isolation and hostname isolation

- User namespace: UID/GID mappings and capability scoping

User namespaces are worth calling out. They let you map “root inside the container” to an unprivileged UID on the host. This changes the meaning of privilege. Rootless containers get a real security win here, because an accidental “root in the container” does not automatically mean “root on the host.”

But it’s still the same kernel boundary. A kernel bug is a kernel bug.

Capabilities

Linux breaks “root” into capabilities (fine-grained privileges). Containers typically start with a reduced capability set, but they often still include enough power to hurt you if you hand out the wrong ones.

The infamous one is CAP_SYS_ADMIN. It gates a huge, loosely-related collection of privileged operations, and in practice it often unlocks dangerous kernel interfaces. That’s why you’ll hear people say “SYS_ADMIN is the new root.”

In real sandboxes, treat capability grants as part of your attack surface budget. The easiest win is often just removing capabilities you don’t need.

Cgroups

Cgroups (control groups) limit and account for resources:

- CPU quota/shares and CPU affinity sets

- memory limits

- I/O bandwidth / IOPS throttling

- max process count (mitigates fork bombs)

Cgroups are primarily about preventing resource exhaustion. They don’t materially reduce kernel attack surface.

Seccomp

Seccomp is syscall filtering. A process installs a BPF program that runs on syscall entry; it can inspect the syscall number (and, in many profiles, arguments) and decide what happens: allow, deny, log, trap, kill, or notify a supervisor.

A tight seccomp profile blocks syscalls that expand kernel attack surface or enable escalation (ptrace, mount, kexec_load, bpf, perf_event_open, userfaultfd, etc). It also tends to block legacy interfaces that are hard to sandbox safely.

As a toy example, a “deny dangerous syscalls” seccomp rule often looks like:

{

"defaultAction": "SCMP_ACT_ALLOW",

"syscalls": [

{ "names": ["bpf", "perf_event_open", "kexec_load"], "action": "SCMP_ACT_ERRNO" }

]

}

In real sandboxes you also filter arguments (clone3 flags, ioctl request numbers) and you run an allowlist rather than a denylist.

There’s one more seccomp feature worth knowing because it shows up in sandboxes: seccomp user notifications (SECCOMP_RET_USER_NOTIF). Instead of simply allowing or denying, the kernel can pause a syscall and send it to a supervisor process for a decision. That lets you build “brokered syscalls” (e.g., only allow open() if the path matches a policy, or proxy network connects through a policy engine).

This is powerful, but it’s not free: brokered syscalls add latency and complexity, and your broker becomes part of the trusted computing base.

But the bottom line stays the same: the syscalls you do allow still execute in the host kernel.

How containers combine these

A “container” is just a regular process configured with a set of kernel policies plus a root filesystem:

- Namespaces scope/virtualize resources.

- Capabilities are reduced.

- Cgroups cap resource usage.

- Seccomp filters syscalls on entry.

- A root filesystem provides the container’s view of

/ (often layered via overlayfs).

- AppArmor/SELinux may apply additional policy.

Conceptually: syscalls enter the host kernel. Seccomp can block them before dispatch. Namespaces scope resources. Cgroups enforce quotas. But it’s still the same host kernel.

This is policy-based restriction within a shared kernel boundary. You reduce what the process can see (namespaces), cap what it can consume (cgroups), and restrict which syscalls it can invoke (seccomp). You do not insert a stronger isolation boundary.

So why do people treat containers as a security boundary? Because “isolated” gets conflated with “secure,” and because containers are operationally convenient.

But if you’re choosing a sandbox, the boundary matters more than convenience.

Where containers fail

I want to be direct: containers are not a sufficient security boundary for hostile code. They can be hardened, and that matters. But they still share the host kernel.

The failure modes I see most often are misconfiguration and kernel/runtime bugs — plus a third one that shows up in AI systems: policy leakage.

Misconfiguration escapes

Many container escapes are self-inflicted. The runtime offers ways to weaken isolation, and people use them.

--privileged removes most guardrails. It effectively turns the container into “root on the host with some extra steps.” If your sandbox needs privileged mode, you don’t have a sandbox.

The Docker socket (/var/run/docker.sock) is another classic. Mount it and you can ask the host Docker daemon to create a new privileged container, mount the host filesystem, and so on. In practice, access to the Docker socket is access to host root.

Sensitive mounts and broad capabilities are the rest of the usual list:

- writable

/sys or /proc/sys

- host paths bind-mounted writable

- adding broad capabilities (especially

CAP_SYS_ADMIN)

- joining host namespaces (

--pid=host, --net=host)

- device passthrough that exposes raw kernel interfaces

These are tractable problems: you can audit configs and ban obvious foot-guns.

Kernel and runtime bugs

A properly configured container still shares the host kernel. If the kernel has a bug reachable via an allowed syscall, filesystem path, network stack behavior, or ioctl, code inside the container can trigger it.

Examples of container-relevant local privilege escalations:

- Dirty COW (CVE-2016-5195): copy-on-write race in the memory subsystem.

- Dirty Pipe (CVE-2022-0847): pipe handling bug enabling overwriting data in read-only mappings.

- fs_context overflow (CVE-2022-0185): filesystem context parsing bug exploited in container contexts.

Seccomp reduces exposure by blocking syscalls, but the syscalls you allow are still kernel code. Docker’s default seccomp profile is a compatibility-biased allowlist: it blocks some high-risk calls but still permits hundreds.

And it’s not only the kernel. A container runtime bug can be enough (for example, runC overwrite: CVE-2019-5736).

Policy leakage (the AI-specific one)

A lot of “agent sandbox” failures aren’t kernel escapes. They’re policy failures.

If your sandbox can read the repo and has outbound network access, the agent can leak the repo. If it can read ~/.aws or mount host volumes, it can leak credentials. If it can reach internal services, it can become a lateral-movement tool.

This is why sandbox design for agents is often more about explicit capability design than about “strongest boundary available.” Boundary matters, but policy is how you control the blast radius when the model does something dumb or malicious prompts steer it.

Two practical notes:

- Rootless/user namespaces help. They reduce the damage from accidental privilege. They don’t make kernel bugs go away.

- Multi-tenant changes everything. If you run code from different trust domains on the same kernel, you should assume someone will try to hit kernel bugs and side channels. “But it’s only build code” stops being a comfort.

One more container-specific gotcha: ioctl is a huge surface area. Even if you block dangerous syscalls, many real kernel interfaces live behind ioctl() on file descriptors (filesystems, devices, networking). If you pass through devices (especially GPUs), you’re exposing large driver code paths to untrusted input.

This is why many “AI sandboxes” that look like containers end up quietly adding one of the stronger boundaries underneath: either gVisor to reduce host syscalls, or microVMs to put a guest kernel in front of the host.

None of this means containers are “bad.” It means containers are a great tool when all code inside the container is in the same trust domain as the host. If you’re running your own services, that’s often true.

The moment you accept code from outside your trust boundary (users, agents, plugins), treat “shared kernel” as a conscious risk decision — not as the default.

Hardening options

Hardening tightens policy. It doesn’t change the boundary.

| Hardening measure | What it does | What it doesn’t do |

|---|

| Custom seccomp | blocks more syscalls/args than defaults | doesn’t protect against bugs in allowed kernel paths |

| AppArmor/SELinux | constrains filesystem/procfs and sensitive ops | doesn’t fix kernel bugs; it only reduces reachable paths |

| Drop capabilities | removes privileged interfaces (avoid SYS_ADMIN) | doesn’t change shared-kernel boundary |

| Read-only rootfs | prevents writes to container root | doesn’t prevent in-memory/kernel exploitation |

| User namespaces | maps container root to unprivileged host UID | kernel bugs may still allow escalation |

At the limit, you can harden a container until it’s nearly unusable. You still haven’t changed the boundary. The few syscalls you allow are still privileged kernel code. The kernel is still shared.

If a kernel exploit matters, you need a different boundary:

- gVisor: syscall interposition

- microVMs: guest kernel behind virtualization

- Wasm/isolates: no syscall ABI at all

Stronger boundaries

Containers share a fundamental constraint: the workload’s syscalls go to the host kernel. To actually change the boundary, you have two main approaches:

- Syscall interposition: intercept syscalls before they reach the host kernel, reimplement enough of Linux in userspace

- Hardware virtualization: run a guest kernel behind a VMM/hypervisor, reduce host exposure to VM exits and device I/O

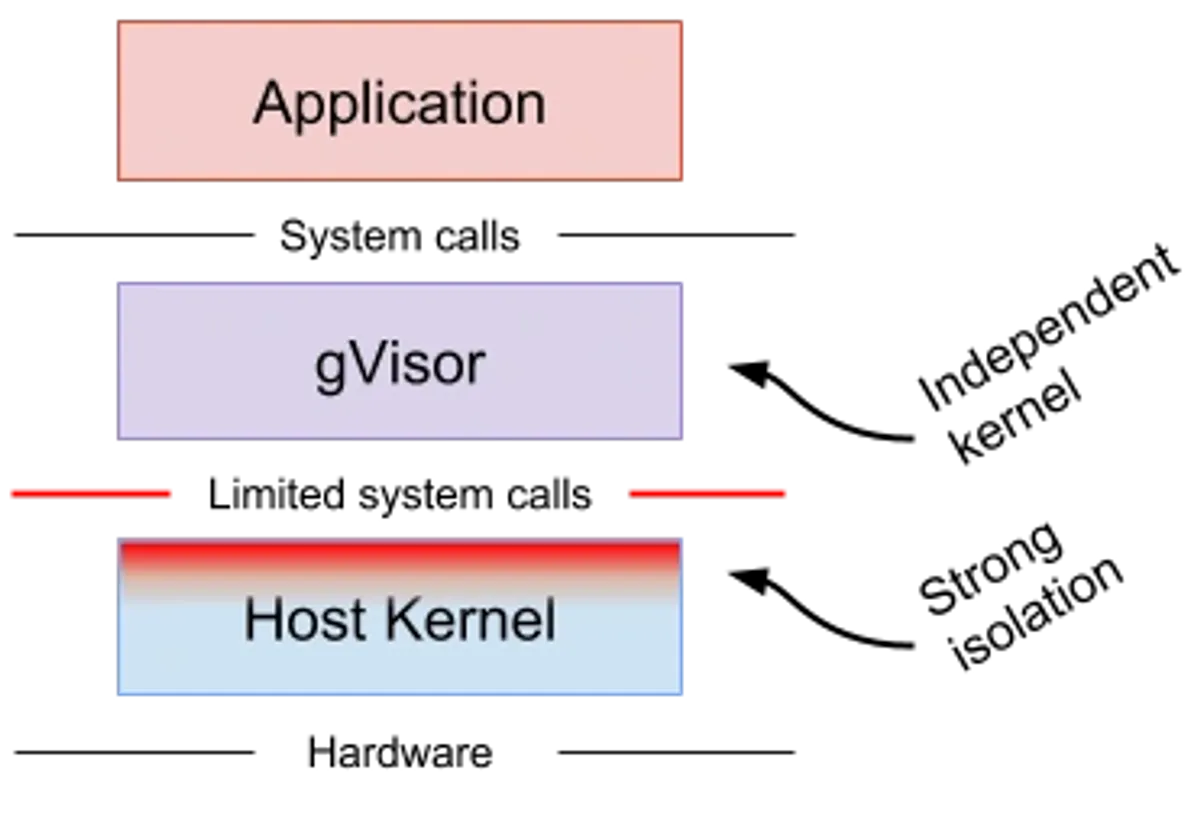

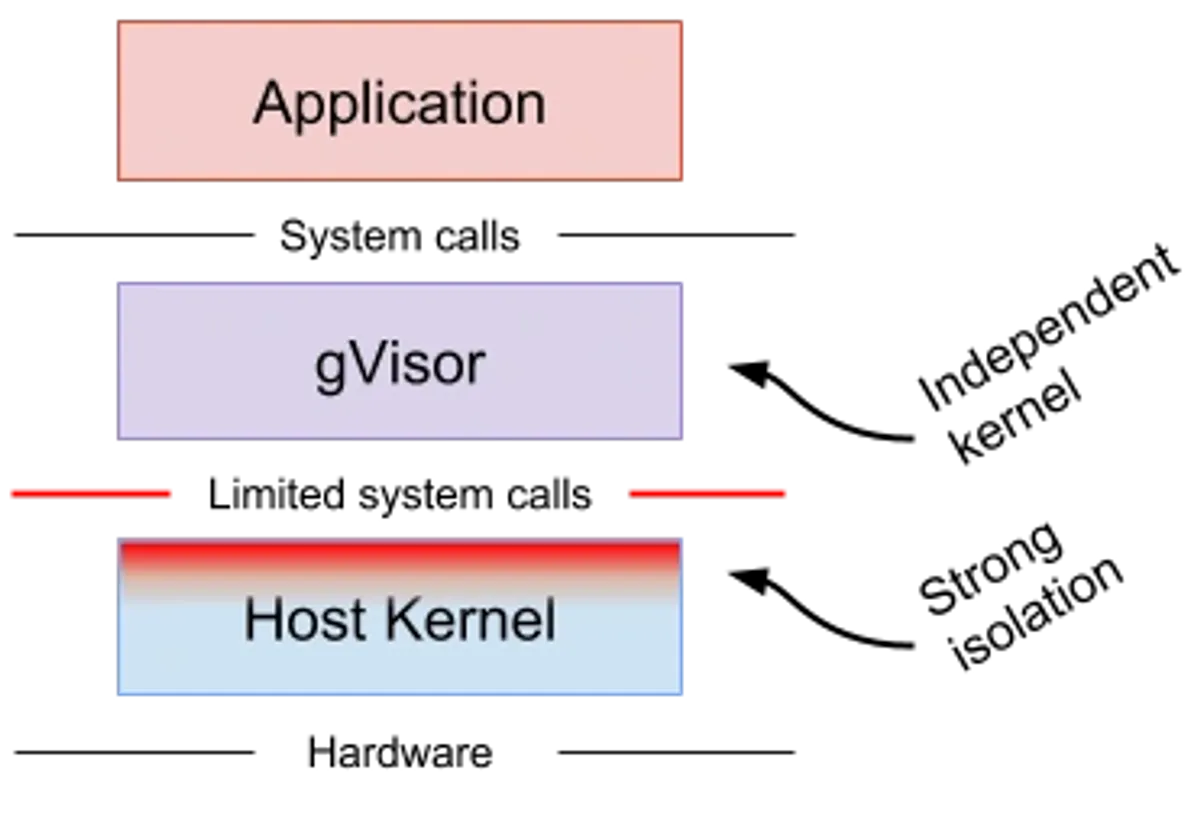

gVisor

gVisor is an “application kernel” that intercepts syscalls (and some faults) from a container and handles them in a userspace kernel called the Sentry.

If containers are “processes in namespaces,” gVisor is “processes in namespaces, but their syscalls don’t go straight to the host kernel.”

A few implementation details matter when you’re choosing it:

- gVisor integrates as an OCI runtime (

runsc), so it drops into Docker/Kubernetes.

- The Sentry implements kernel logic in Go: syscalls, signals, parts of

/proc, a network stack, etc.

- Interception is done by a gVisor platform. Today the default is systrap; older deployments used ptrace, and there is optional KVM mode.

Two subsystems are worth understanding because they dominate performance and security behavior:

Filesystem mediation (Gofer / lisafs). gVisor commonly splits responsibilities: the Sentry enforces syscall semantics, but filesystem access may be mediated by a separate component that does host filesystem operations and serves them to the Sentry over a protocol (historically “Gofer”; newer work includes lisafs). This is one way gVisor keeps the Sentry’s host interface small and auditable.

Networking (netstack vs host). gVisor can use its own userspace network stack (“netstack”) and avoid interacting with the host network stack in the same way a container would. There are also modes that integrate more directly with host networking depending on deployment constraints.

The security point is that the workload no longer chooses which host syscalls to call. The Sentry does, and the Sentry itself can be constrained to a small allowlist of host syscalls. gVisor has published syscall allowlist figures: 53 host syscalls without networking, plus 15 more with networking (68 total) in one configuration, enforced with seccomp on the Sentry process.

That’s a very different interface than “whatever syscalls your container workload can make.”

The tradeoffs are predictable:

- Compatibility: not every syscall and kernel behavior is identical. There’s a syscall compatibility table, and you will eventually hit it.

- Overhead: syscall interposition isn’t free. Syscall-heavy workloads pay more. Filesystem-heavy workloads pay for mediation and extra copies/IPC.

- Debuggability: failure modes include

ENOSYS for unimplemented calls, or subtle semantic mismatches.

My take: gVisor fits best when you can tolerate “Linux, but with a compatibility matrix,” and you want a materially smaller host-kernel interface than a standard container.

MicroVMs

The alternative to syscall interposition is hardware isolation. Run a guest kernel behind hardware virtualization (KVM on Linux, Hypervisor.framework on macOS). The host kernel sees VM exits and virtio device I/O rather than individual workload syscalls.

This is why microVMs are the default answer for “run arbitrary Linux code for strangers.” You get full Linux semantics without reimplementing the syscall ABI.

What the host kernel actually sees

A microVM still uses the host kernel, but the interface changes shape:

- VMM makes

/dev/kvm ioctls to create vCPUs, map guest memory, and run the VM.

- Guest interacts with virtual devices (virtio-net, virtio-blk, vsock). Those devices are implemented by the VMM (or by backends like vhost-user).

- Execution triggers VM exits (traps to the host) on privileged events, device I/O, interrupts, etc.

The host kernel still mediates access, but through a narrower, more structured interface than the full Linux syscall ABI.

What microVMs don’t solve by themselves

A guest kernel boundary doesn’t automatically mean “safe.”

You still need to decide policy:

- Does the guest have outbound network access?

- Does it mount secrets or credentials?

- Does it have access to internal services?

- Does it share any filesystem state between runs?

A microVM is a strong boundary, but you still need a strong policy to avoid turning it into a high-powered data exfiltration box.

At scale, microVM-based sandboxes converge on a small set of lifecycle patterns:

- Ephemeral session VM: boot → run commands → destroy. Simple and dependable.

- Snapshot cloning: boot a “golden” VM once (language runtimes, package cache) → snapshot → clone per session. Fast cold start and fast reset.

- Fork-and-exec style: keep a pool of paused/suspended VMs, resume on demand. Operationally trickier but can reduce tail latency.

State injection is also a design choice, not a given:

- Block device images (ext4 inside a virtio-blk): simple, portable, snapshot-friendly.

- virtio-fs / 9p-like shares: share a host directory into the guest (useful for “workspace mirrors,” but it reintroduces host FS as part of the policy surface).

- Network fetch: pull code into the guest from an object store/Git remote. Keeps host FS out of the guest boundary, but requires network policy.

And you still need a network story. Common patterns:

- NAT + egress allowlist: most common for SaaS agents.

- No direct internet: force all traffic through a proxy that enforces policy and logs.

- Dedicated VPC/subnet: isolate “untrusted execution” away from internal services.

Finally, if you care about protecting the guest from the host (e.g., “users don’t trust the operator”), look at confidential computing (SEV-SNP/TDX) and projects like Confidential Containers. That’s a different threat model, but it’s increasingly relevant for hosted agent execution.

What is a VMM?

On Linux, “VM” is two layers:

- KVM (in kernel): turns Linux into a hypervisor and exposes virtualization primitives via

/dev/kvm ioctls.

- VMM (userspace): allocates guest memory, configures vCPUs, and provides the virtual devices the guest uses.

QEMU is the classic general-purpose VMM: tons of devices, tons of legacy paths, tons of code. That flexibility is useful — and it’s also an attack surface and an ops cost.

MicroVM VMMs cut that down on purpose: fewer devices, fewer emulation paths, smaller footprint, faster boot.

The device model is the new interface

Moving from “container syscalls” to “microVM” shifts attack surface rather than eliminating it.

Instead of worrying about every syscall handler in the host kernel, you worry about:

- KVM ioctl handling in the host kernel,

- the VMM process (its parsing of device config, its event loops),

- and the virtual device implementations (virtio-net, virtio-blk, virtio-fs, vsock).

This is why microVM VMMs are aggressive about minimal devices. Every device you add is more parsing, more state machines, more edge cases.

It also changes your patching responsibility. With microVMs, you now have two kernels to keep healthy:

- the host kernel (KVM and related subsystems),

- and the guest kernel (what your untrusted code actually attacks first).

The guest kernel can be slimmer than a general distro kernel: disable modules you don’t need, remove filesystems you don’t mount, avoid exotic drivers. This doesn’t replace patching, but it shrinks reachable code.

Virtio, but which flavor?

Virtio devices can be exposed via different transports. Firecracker uses virtio-mmio (simple, minimal) while other VMMs commonly use virtio-pci (more “normal VM” shaped, broader device ecosystem). You usually don’t care until you do: some guest tooling assumes PCI, some performance features assume a certain stack, and passthrough work tends to be PCI-centric.

“MicroVM” describes a design stance: remove legacy devices and keep the device model small.

Firecracker

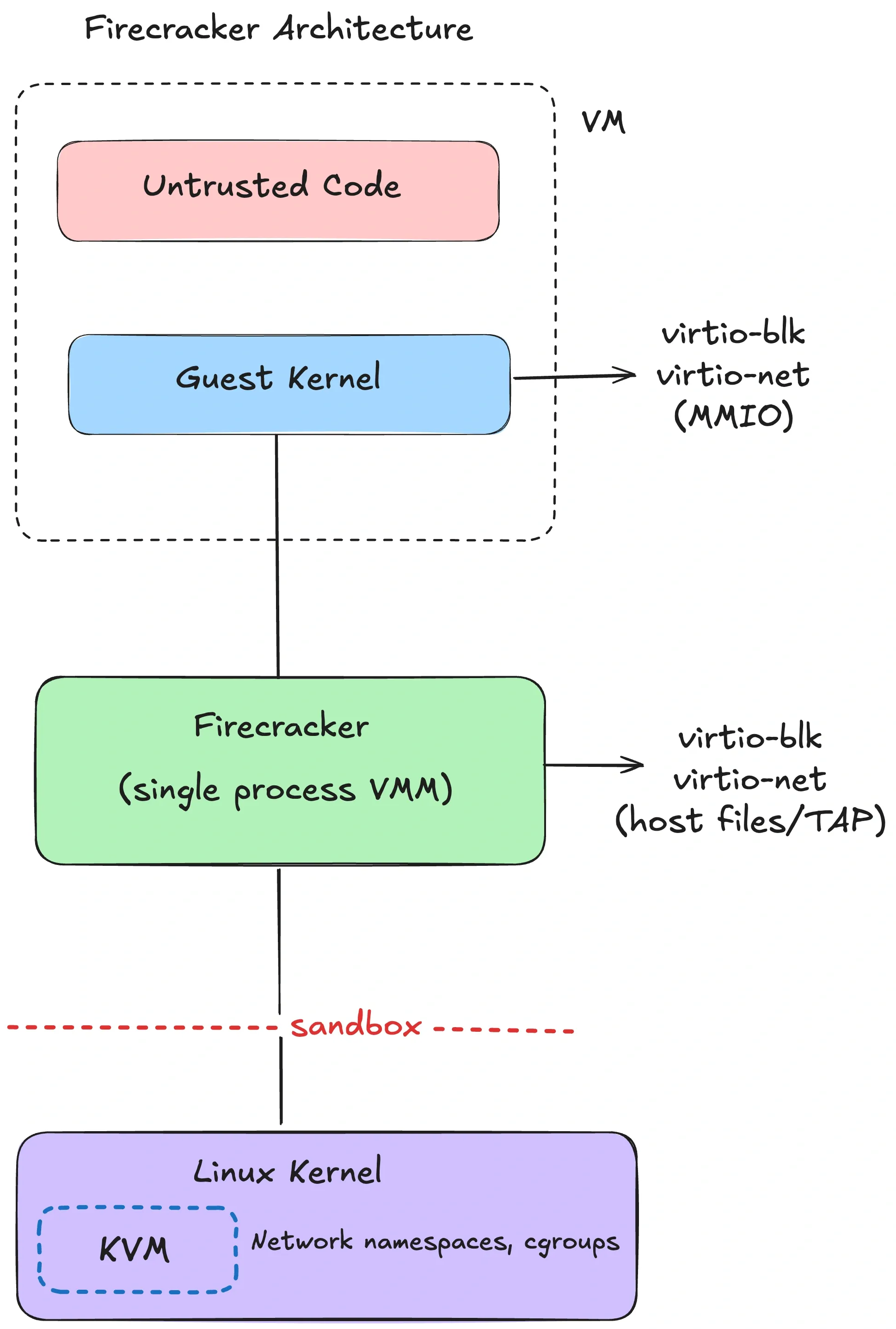

Firecracker is AWS’s minimalist VMM for multi-tenant serverless (Lambda, Fargate). It’s purpose-built for running lots of small VMs with tight host confinement.

The architecture is intentionally boring:

- one Firecracker process per microVM,

- minimal virtio device model (net, block, vsock, console),

- and a “jailer” that sets up isolation for the VMM process before the guest ever runs.

Internally you can think of three thread types:

- an API thread (control plane),

- a VMM thread (device model and I/O),

- vCPU threads (running the KVM loop).

The security story is defense in depth around the VMM:

- The jailer sets up chroot + namespaces + cgroups, drops privileges, then execs the VMM.

- A tight seccomp profile constrains the VMM. The Firecracker NSDI paper describes a whitelist of 24 syscalls (with argument filtering) and 30 ioctls.

A Firecracker microVM is configured with a small API surface (REST API or socket). Typical “remote devbox” products build higher-level lifecycle around that API: boot, snapshot, restore, pause, resume, collect logs.

Example: the VMM doesn’t “mount your repo.” You decide how to inject state: attach a block device, mount a virtio-fs share, or pull code via network inside the guest. Those choices are policy choices.

Snapshot/restore is a practical win for agents and RL:

- Agents: you can pre-warm a base image (language runtimes, package cache) and clone quickly.

- RL: you can reset to a known state without replaying a long initialization sequence.

Firecracker supports snapshots, but snapshot performance and correctness are workload-sensitive (memory size, device state, entropy sources). Treat it as “works well for many cases,” not “free.”

A few pragmatic limitations to keep in mind:

- Firecracker focuses on modern Linux guests. It intentionally avoids a lot of “PC compatibility” hardware.

- The device set is minimal by design. If your workload depends on obscure devices or kernel modules, you’ll either adapt the guest or choose a different VMM.

- Debugging looks more like “debug a tiny VM” than “debug a container.” You’ll want good serial console logs and metrics from the VMM.

And a nuance that matters: “125ms boot” is usually the VMM and guest boot path. If you’re launching Firecracker via a heavier control plane (containerd, network setup, storage orchestration), end-to-end cold start can be higher. Measure in your stack.

cloud-hypervisor

cloud-hypervisor is also a Rust VMM, built from the same rust-vmm ecosystem, but it targets a broader class of “modern cloud VM” use cases.

The delta vs Firecracker is features and device model:

- PCI-based virtio devices (no virtio-mmio)

- CPU/memory/device hotplug

- optional vhost-user backends (move device backends out-of-process)

- VFIO passthrough (including GPUs, with the usual IOMMU/VFIO constraints)

- Windows guest support

If you need “VM boundary and GPU passthrough,” this is a common landing spot. The project advertises boot-to-userspace under 100ms with direct kernel boot.

A caution on GPU passthrough: VFIO gives the guest much more direct access to hardware. That can be necessary and still safe, but it changes the failure modes. You now care about device firmware, IOMMU isolation, and hypervisor configuration in ways you don’t in “CPU-only microVM” designs. Many systems choose a hybrid: CPU-only microVMs for general code execution and a separate GPU service boundary for model execution.

libkrun

libkrun takes a different approach: it’s a minimal VMM embedded as a library with a C API. It uses KVM on Linux and Hypervisor.framework on macOS/ARM64.

This shows up in “run containers inside lightweight VMs on my laptop” tooling, and it’s relevant because local agents are increasingly a first-class workflow. libkrun also has an interesting macOS angle: virtio-gpu + Mesa Venus to forward Vulkan calls on Apple Silicon (Vulkan→MoltenVK→Metal). In many setups, this is how some container stacks get GPU acceleration on macOS without “full fat” VM managers.

The catch is that the trust boundary can be different. With an embedded VMM, you need to treat the VMM process itself as part of your TCB and sandbox it like any other privileged helper.

MicroVM options at a glance

| VMM | Best at | Not great at |

|---|

| Firecracker | multi-tenant density, tight host confinement, snapshots | general VM features, GPU passthrough |

| cloud-hypervisor | broader VM feature set; VFIO/hotplug; Windows support | smallest possible surface area |

| libkrun | lightweight VMs on dev machines (especially macOS/ARM64) | large-scale multi-tenant control planes |

gVisor vs microVMs

If you’re choosing between “syscall interposition” and “hardware virtualization,” the practical tradeoffs are:

- Compatibility: microVMs are full Linux; gVisor is “mostly Linux” and you need to validate.

- Overhead: gVisor avoids running a guest kernel; microVMs pay for a guest kernel and VMM (but can still be fast).

- Attack surface: gVisor bets on a userspace kernel implementation and a small host syscall allowlist; microVMs bet on KVM + VMM device surface.

There isn’t a universal winner. The threat model and workload profile usually decide.

Kata Containers

Kata solves a common operational constraint: “I want to keep my container workflow, but I need VM-grade isolation.”

Kata Containers is an OCI-compatible runtime that runs containers inside a lightweight sandbox VM (often at the pod boundary in Kubernetes: multiple containers in a pod share one VM).

The architecture in one paragraph:

- containerd/CRI creates a pod sandbox using a Kata runtime shim,

- the shim launches a lightweight VM using a configured hypervisor backend (QEMU, Firecracker, cloud-hypervisor, etc),

- a

kata-agent inside the guest launches and manages the container processes,

- the rootfs is shared into the guest (commonly via virtio-fs),

- networking and vsock are provided via virtio devices.

The appeal is container ergonomics with a guest-kernel boundary. The cost is overhead: each sandbox VM carries a guest kernel plus VMM/device mediation, and boot adds latency.

Kata makes sense when you’re running mixed-trust workloads on the same Kubernetes cluster and you want a VM boundary without rewriting your platform.

Operationally, Kata is usually introduced via Kubernetes RuntimeClass: some pods use the default runc container runtime; untrusted pods use the Kata runtime class. That lets you mix trusted and untrusted workloads without standing up a separate cluster.

If you’re exploring confidential computing, Kata is also one of the common integration points for Confidential Containers (hardware-backed isolation like SEV-SNP/TDX). That’s not required for “sandbox hostile code,” but it is relevant if you need tenant isolation and stronger guarantees against the infrastructure operator.

Runtime sandboxes

Now for something genuinely different. Containers, gVisor, and microVMs all run “code as a process,” so the guest sees some syscall ABI (host kernel, userspace kernel, or guest kernel).

Runtime sandboxes flip that model. The boundary lives inside the runtime itself. The sandboxed code never gets the host’s syscall ABI. It only gets whatever the runtime (and embedder) explicitly provides.

WebAssembly

WebAssembly is a bytecode sandbox with a clean capability story. Modules can’t touch the outside world unless the host exposes imports.

That’s a fundamentally different default from “here’s a POSIX process, please behave.”

Wasm runtimes enforce:

- memory isolation: modules operate within a linear memory; out-of-bounds reads/writes trap.

- constrained control flow: no arbitrary jumps to raw addresses.

- no ambient OS access: host calls are explicit imports.

WASI (WebAssembly System Interface) extends this with a capability-oriented API. The signature move is preopened directories: instead of letting the module open arbitrary paths, you hand it a directory handle that represents “this subtree,” and it can only resolve relative paths inside it.

Here’s what that feels like in practice (pseudocode-ish):

// Give the module a view of ./workspace, not the host filesystem.

wasi.preopenDir("./workspace", "/work");

// Allow outbound HTTPS to a specific host.

wasi.allowNet(["api.github.com:443"]);

If you never preopen ~/.ssh, the module can’t read it. There’s no “oops, I forgot to check a path prefix” bug in your app that accidentally grants access, because the capability was never granted.

Performance is often excellent because there’s no guest OS to boot. Instance/module instantiation can be microseconds to milliseconds depending on runtime and compilation mode (AOT vs JIT). That’s why edge platforms like Wasm and isolates: high density, low cold start.

One detail that matters in real sandboxes: resource accounting. A runtime sandbox won’t magically stop infinite loops or exponential algorithms. You still need CPU/time limits. Many runtimes provide “fuel” or instruction metering (e.g., Wasmtime fuel) so you can preempt runaway execution deterministically.

The limitations often show up as “I need one more host function”:

- The real security boundary is your import surface. If you expose a powerful

runCommand() host call, you reinvented a shell.

- Keep imports narrow and typed. Prefer structured operations (“read file X from preopened dir”) over generic ones (“open arbitrary path”).

One reason Wasm keeps showing up in agent tooling is the component model direction: instead of “here’s a module, call exported functions,” you get typed interfaces and better composition. That pushes you toward smaller tools with explicit inputs/outputs — which is exactly what you want for capability-scoped AI tools.

The flip side is that your host still has to be careful. The easiest way to ruin a clean Wasm sandbox is to expose one overly-powerful host function. Capability systems fail by accidental ambient authority.

Practical constraints to consider:

- Threads exist, but support varies by runtime and platform.

- WASI networking has been in flux (Preview 1 vs Preview 2; ecosystem catching up).

- Dynamic languages usually require interpreters (Pyodide, etc).

- Anything that expects “normal Linux” (shells, package managers, arbitrary binaries) doesn’t port cleanly.

Major runtimes, if you’re evaluating:

- Wasmtime (Bytecode Alliance): security-focused, close to WASI/component-model work.

- Wasmer: runtime plus tooling ecosystem, with WASIX for more POSIX-like APIs.

- WasmEdge: edge/cloud-native focus.

V8 isolates (and deny-by-default runtimes)

V8 isolates are isolated instances of the V8 JavaScript engine within a process. Platforms like Cloudflare Workers use isolates to run many tenants at high density, with low startup overhead.

The isolation boundary here is the runtime: separate heaps and globals per isolate, with controlled ways to share or communicate.

Production systems still layer OS-level defenses for defense in depth (namespaces/seccomp around the runtime process, broker processes for I/O, mitigations for timing side channels). The runtime boundary is powerful, but it’s not a replacement for OS isolation if your threat model includes engine escapes.

Deno’s permission model is the same pattern exposed to developers: V8 plus a deny-by-default capability model (--allow-read, --allow-net, --allow-run).

The limitation is scope: isolates are for JS/TS (and embedded Wasm). If your sandbox needs arbitrary ELF binaries, this isn’t the tool.

Who uses runtime sandboxes for AI?

The pattern that keeps showing up is Wasm for tool isolation, not “Wasm as a whole dev environment”:

- Microsoft Wassette: runs Wasm Components via MCP with a deny-by-default permission model.

- NVIDIA: describes using Pyodide (CPython-in-Wasm) to run LLM-generated Python client-side inside the browser sandbox.

- Extism: a Wasm plugin framework that’s basically “capability-scoped untrusted code execution.”

When runtime sandboxes are enough

Runtime sandboxes fit a specific profile:

| Constraint | Runtime sandbox strength |

|---|

| Stateless execution | excellent |

| Cold start / density | excellent |

| Full Linux compatibility | no (explicit host APIs only) |

| Language flexibility | limited (Wasm languages / JS) |

| GPU access | only via host-provided APIs (e.g., WebGPU), not raw devices |

If the product needs a full userspace and arbitrary binaries, you’ll end up back at microVMs or gVisor. If the product is “run small tools safely,” runtime sandboxes can be the cleanest option.

Choosing a sandbox

Most selection mistakes come from skipping the boundary question and jumping straight to implementation details.

Here’s how I actually decide:

- Threat model: is this code trusted, semi-trusted, or hostile? Does a kernel exploit matter?

- Compatibility: do you need full Linux semantics, or can you live inside a capability API?

- Lifecycle: do you need fast reset/snapshots, or long-lived workspaces?

- Operations: can you run KVM and manage guest kernels, or are you constrained to containers?

A decision table:

| Workload | Threat model | Compatibility needs | Recommended boundary |

|---|

| AI coding agent (multi-tenant SaaS) | hostile (user-submitted code) | full Linux, shell, package managers | microVM (Firecracker / cloud-hypervisor) |

| AI coding agent (single-tenant / self-hosted) | semi-trusted | full Linux | hardened container or gVisor |

| RL rollouts (parallel, lots of resets) | mostly trusted code, needs isolation per run | fast reset, snapshot/restore | microVM with snapshot support |

| Code interpreter (stateless snippets) | hostile | scoped capabilities, no shell | gVisor or runtime sandbox (if language fits) |

| Tool calling / plugins | mixed | explicit capability surface | Wasm / isolates |

Two common mistakes I see:

Mistake 1: “Our code is trusted.” In agent systems, the code you run is shaped by untrusted input (prompt injection, dependency confusion, supply chain). Treat “semi-trusted” as the default unless you have a strong reason not to.

Mistake 2: “We’ll just block the network.” Network restrictions matter, but they’re not a boundary. If you’re running hostile code on a shared kernel, the “no network” sandbox can still become a kernel exploit sandbox.

Before picking a boundary, I also write down a minimum viable policy. If you can’t enforce these, you don’t have a sandbox yet:

- Default-deny outbound network, then allowlist. (Or route everything through a policy proxy.)

- No long-lived credentials in the sandbox. Use short-lived scoped tokens.

- Workspace-only filesystem access. No host mounts besides what you explicitly intend.

- Resource limits: CPU, memory, disk, timeouts, and PIDs.

- Observability: log process tree, network egress, and failures. Sandboxes without telemetry become incident-response theater.

Concrete defaults, if you’re starting from scratch:

- Multi-tenant AI agent execution: microVMs. Firecracker for density and a tight VMM surface. cloud-hypervisor if you need VFIO/hotplug/GPU.

- “I already run Kubernetes”: gVisor is a good middle ground if compatibility is acceptable.

- Trusted/internal automation: hardened containers are usually fine.

- Capability-scoped tools: Wasm or isolates.

A quick rule of thumb that holds up surprisingly well:

- If you need a shell + package managers and you don’t fully trust the code: start at microVM.

- If you can live inside a compatibility matrix to save overhead: consider gVisor.

- If you can model the task as capability-scoped operations: prefer Wasm/isolate.

Then validate with measurement: cold start, steady-state throughput, and operational complexity. MicroVMs can be cheap at scale, but only if your orchestration is built for it.

The point isn’t to crown a winner. It’s to know what would have to fail for an escape to happen, and to pick the boundary that matches that reality.

Appendix: Local OS sandboxes

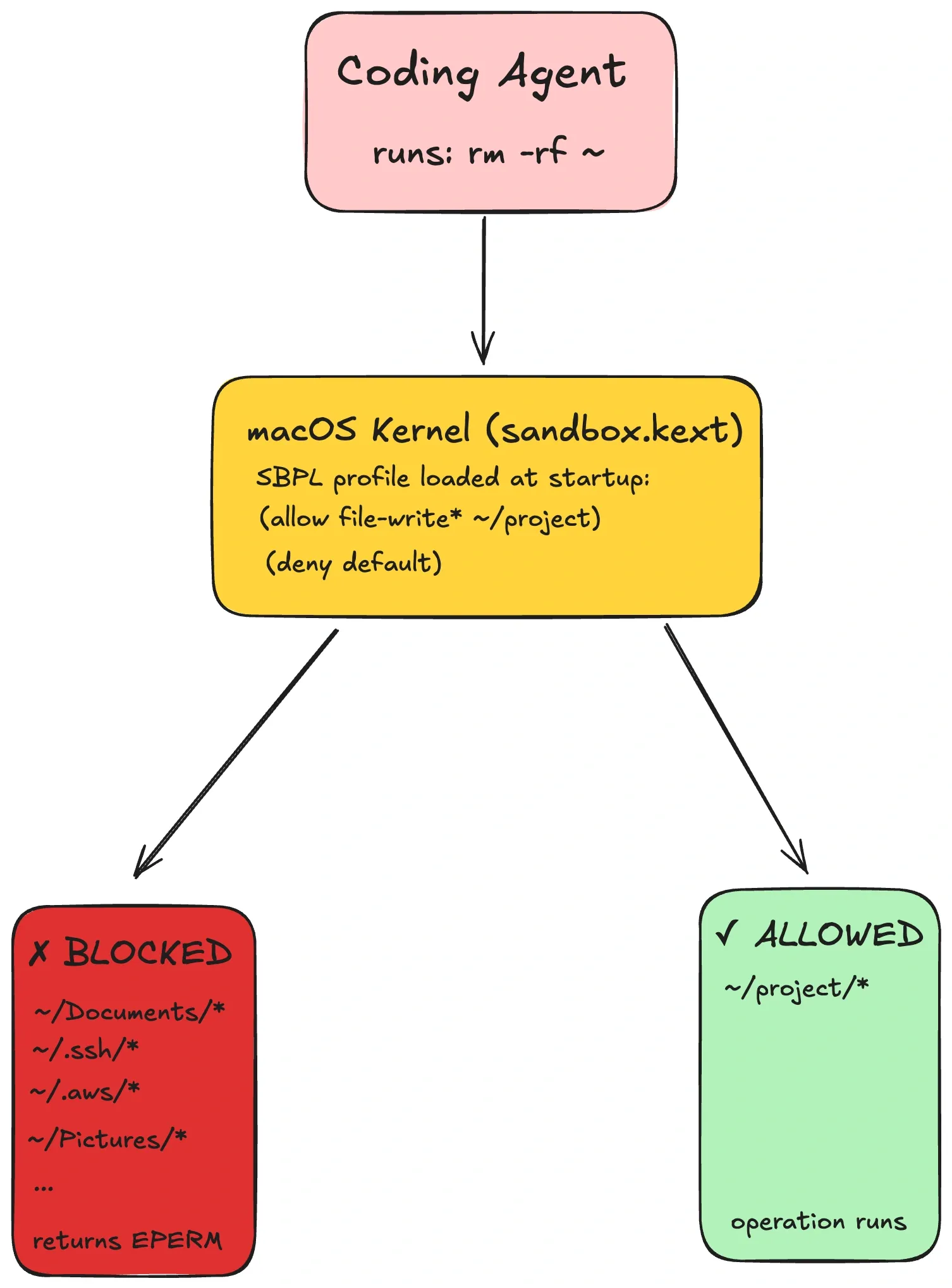

Everything above assumes you’re running workloads on a server. Local agents (Claude Code, Codex CLI, etc.) are a different problem:

The agent runs on your laptop. It can see your filesystem. In this case, the failure mode is often not “kernel 0-day.” It’s “prompt injection tricks the agent into reading ~/.ssh or deleting your home directory.”

Each major OS has a mechanism for “lightweight, per-process” sandboxing. These are still policy enforcement within a shared kernel boundary, but they’re designed to be user-invocable and fast.

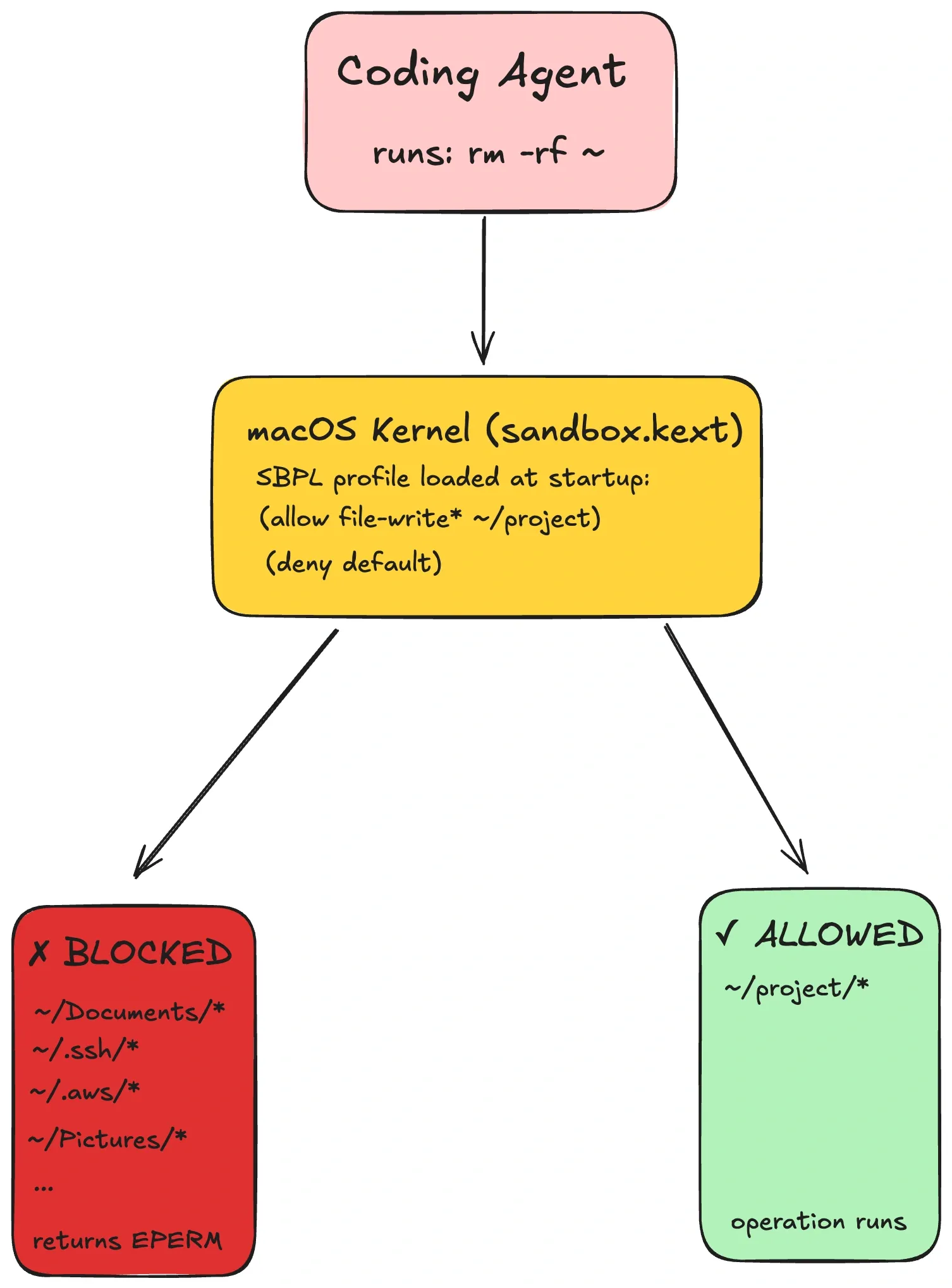

macOS Seatbelt (App Sandbox)

Seatbelt is macOS’s kernel-enforced sandbox policy system (SBPL profiles). Tools can generate a profile that allows the workspace and temp directories, and denies sensitive paths like ~/.ssh. When the agent tries anyway, the kernel returns EPERM. The shell can’t “escape” a kernel check.

A note on tooling: sandbox-exec has been deprecated for years, but the underlying mechanism is still used across Apple’s platforms. Modern tools tend to apply sandboxing via APIs/entitlements rather than via a CLI wrapper.

A tiny SBPL example looks like:

(version 1)

(deny default)

(allow file-read* (subpath "/Users/alice/dev/myrepo"))

(allow network-outbound (remote tcp "api.github.com:443"))

Linux Landlock (+ seccomp)

Landlock is an unprivileged Linux Security Module designed for self-sandboxing: a process can restrict its own filesystem access (and, on newer kernels, some TCP operations), and the restriction is irreversible and inherited by children.

In most setups, Landlock pairs well with seccomp: Landlock controls filesystem paths; seccomp blocks high-risk syscalls (ptrace, mount, etc).

At the API level, Landlock is a few syscalls: create a ruleset → add path rules → enforce. A minimal flow looks like:

int ruleset_fd = landlock_create_ruleset(&attr, sizeof(attr), 0);

landlock_add_rule(ruleset_fd, LANDLOCK_RULE_PATH_BENEATH, &rule, 0);

landlock_restrict_self(ruleset_fd, 0);

The important behavior is that the restriction is one-way (can’t be disabled) and inherited by children. That makes it suitable for “run this tool, but don’t let it touch anything else.”

If you want a practical tool to start with, landrun wraps Landlock into a CLI. It requires Linux 5.13+ for filesystem rules and 6.7+ for TCP bind/connect restrictions.

Windows AppContainer

AppContainer is Windows’ capability-based process isolation (SIDs/tokens). It’s widely used for browser renderer isolation. AppContainer processes run with a restricted token and only the capabilities you grant (network, filesystem locations, etc).

For coding agents it’s less common today mostly because setup is Win32-API heavy compared to “write a profile / apply a ruleset.” But if you need strong OS-native isolation on Windows without spinning up VMs, it’s the primitive to learn.

Comparison

| Aspect | macOS Seatbelt | Linux Landlock + seccomp | Windows AppContainer |

|---|

| Privilege required | none | none | none (but setup is explicit) |

| Filesystem control | profile rules | path rulesets | capability grants |

| Network control | profile + proxy patterns | namespaces/seccomp (or limited Landlock) | capability grants |

| What it doesn’t solve | kernel vulnerabilities | kernel vulnerabilities | kernel vulnerabilities |

One operational pitfall across all local sandboxes: you have to allow enough for the program to function. Dynamic linkers, language runtimes, certificate stores, and temp directories are all “real” dependencies. A deny-by-default sandbox that forgets /usr/lib (or the Windows equivalent) will fail in confusing ways.

Treat profiles as code: version them, test them, and expect them to evolve as your agent’s needs change.

I personally run my code agents only with a sandbox enabled and do advise others to do the same.